Benefits

On this page:

- Benefits of urban trees

- Benefits of urban parks

- How our plans complement Glasgow City Council’s 2050 strategy

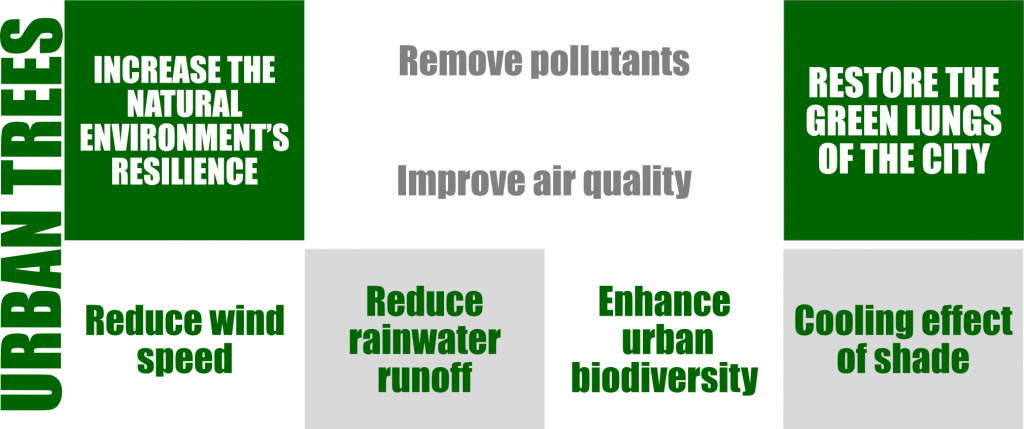

Urban Trees

- Increase the natural environment’s resilience

- Reduce wind speed

Remove pollutants

- Studies have suggested that urban greenery can reduce noise, ozone levels, personal exposure to particulates, and mitigate some of the additional harmful effects of air pollution matter (b)

- Each year, London’s trees removed 2.4 million tonnes of air pollution, including carbon dioxide, dust and other toxins(g)

- Improve air quality

- Reduce rainwater runoff

- Enhance urban biodiversity

- Restore the green lungs of the city

Cooling effect of shade

- A 2010 review of the role of greener environments on mitigating high air temperature in urban areas found, on average, a park was 0.94°C cooler in the day than the surrounding built environment. (b)

Urban Parks

Reduce burden on NHS

- Reconnecting with the environment can help everyone develop healthier lifestyles and prevention of poor health/illness (a)

- Across eight European cities, people were 40% less likely to be obese in the greenest areas, after controlling for a range of relevant factors (b)

- There is a significant volume of evidence showing that a greater quantity and proximity of the natural environment (mainly in relation to living environment) is consistently positively associated with health outcomes. Understanding of a potential dose-response relationship is limited but growing. (b)

- A study in the Netherlands looked at physician-assessed morbidity in 196 Dutch general practices, for 24 disease clusters, and after controlling for socio-economic factors found that disease prevalence was lower the more green space there was in a 1km radius (Maas et al 2009 in (c))

- In studies relating to obesity there is a positive association between access to greenspace and physical activity, weight and associated health conditions (Lachowycz and Jones 2011 in (c))

Improve mental health

- Contact with nature can improve sleep patterns, reduce stress, improve mood and self-esteem, as well as providing meaningful social contact (a)

- There is relatively strong and consistent evidence for mental health and wellbeing benefits arising from exposure to natural environments, including reductions in stress, fatigue, anxiety and depression, together with evidence that these benefits may be most significant for marginalised groups. (b)

Improve physical health

- The outdoors brings a range of benefits to people living with dementia and their carers (a)

- better motor skills for children who play in green spaces; reduced symptoms of ADHD with contact with green spaces; more likelihood of physically active young people in greener and more walkable neighbourhoods (a)

- Encouraging interest in the natural world and outdoor activity early in life has a positive role in supporting more active, healthier lifestyles in adult life (a)

- An extensive and robust body of evidence suggests that living in greener environments (e.g. greater percentage of natural features around the residence) is associated with reduced mortality (b)

- Self-rated health has also been shown to be higher in those living in places with a greater proportion of good quality natural environments (indicators included bird species richness and percentage of protected and designated landcover). (b)

- Some of the strongest evidence concerns the importance of direct contact with nature to the development of a healthy microbiome…studies have determined that exposure to diverse natural habitats is critical for development of a healthy microbiome. (b)

- Natural environments are associated with and may support higher levels of physical activity and therefore physical health. (b)

- The great outdoors, therefore, should not be just considered a playground for those who seek the thrills of extreme sports, but emphasis should be placed on access for all. One way of doing this is to ensure urban parks are maintained and are developed to produce interesting areas of high biodiversity, as well as more open play areas, where more sports may be played, increasing opportunities for exercise. Not only may both types of area elicit greater health benefits, but also may offer protection for the natural environment and preserve species (d).

- People living closer to green spaces are more physically active, and are less likely to be overweight or obese, and people who lived furthest from public parks were 27% more likely to be overweight or obese. (e)

Enhance the community

- Increased opportunities to make social contact, increase inter-generational connections, avoid isolation…can enhance community cohesion. Experience and involvement in care of the outdoors can lead to stronger, more inclusive and sustainable communities (a)

- Noise Reduction

- Aesthetic appeal

- Encourage Active Travel

Financial benefits

- In Edinburgh, the council estimates that for every £1 invested in a park, there is a £12 benefit The cost benefit ratio varies from 1:7 for a natural park, to 1:17 for a large city-centre park (j)

- A view of green space from home is estimated to have a health value of £135-452 per person per year (b)

- Garden Partners in Wandsworth (Jackson et al, no date) suggested an estimated potential saving to the NHS in one year of the project to be £113,748 for those who reported an improvement in their health. When widened to include those who reported that their condition was no worse, this gave a potential saving of £500,223 (f)

- In London, it has been estimated that £950 million is saved in healthcare costs because of the city’s green spaces (i)

Interaction with Glasgow City Council Strategy

Executive summary (p3) Vibrant, Liveable, Connected and Green and Resilient.

..six Strategic Place Ambitions.. /../- Reduce traffic dominance and car dependency and create a pedestrian and cycle friendly centre,. – Green the centre and make it climate resilient with a network of high quality public spaces and green/blue infrastructure that caters for a variety of human and climatic needs

1. Introduction (p7)

- A Collaborative Journey ..between Government, City Council, key agencies, ..local residents, ..—that places people at the centre of the city’s transformation.

- Planning /for/people ..multi-functionality of the centre’s physical environment ..to address ..climate change ..attractiveness to investors, workers, res- idents and visitors ..

- Collaborative working ..can empower local people and can unlock creative approaches to ..multi- functional infrastructure (such as ..green/blue drainage systems, .. natural networks, public space, and energy networks).

- /a people-focussed …transformation/..to become a ..healthier, greener, more inclusive ..city.

(p9) – Priority Issues ..-

creation of public space – addressing the severe lack of public spaces in the centre, including child-friendly space. ..- reduce the dominance of the car and negative environmental and ‘place’ impact of vehicular traffic. – Significantly improve the walking and cycling experience ..- reuse and redevelop vacant land .., repair lost walking connections.

(p10) Vision: In 2050,

A green, attractive and walkable city centre will create a people friendly place that fosters creativity, ..promotes social cohesion, environmental /sustainability…/### six strategic place ambitions to –

Green the centre and make it climate resilient with a network of high quality public spaces and green/blue infrastructure that caters for a variety of human and climatic needs

3. Sustainable City Centre (p18) – What we want to achieve ..-

a transformed public realm of walkable, quieter and greener streets linking new and improved public spaces

(p22) Priority Issues ..Improve public environment to tackle issues that inhibit city living; traffic dominated streets, lack of greenery, lack of public spaces, noise and poor air quality

(p23) strategic propositions. ..-

High quality open space, including green and play space – Streets that are more walkable and cycleable, more child- friendly and less traffic dominated

4. Connected City Centre (p26) – want to achieve ..-

- The streets will be greener, cleaner and healthier and contribute to the environmental management of the city; softened by street trees, rain gardens and attractive green spaces and containing less vehicle traffic. ..- A transformed streetscape that is part of an outstanding people friendly and climate resilient environment;

- (p27) Priority ..- Excess car parking, on and off street, ..supporting car-based commuting

5. Green and Resilient (p34) – Place Quality –

- High quality public spaces ..are fundamental to our enjoyment of a city. Feature parks, squares and promenade spaces – for interaction or quiet reflection—alongside rich architectural heritage are key components of sustainable, attractive and globally competitive cities and their centres.

- Open spaces are crucial for health and wellbeing and are vital to support the city centre’s ambition to be more liveable. Green spaces and play spaces are essential neighbourhood components that enable physical activity, engagement with nature and social contact.

- Critically, the ..urban landscape ..must radically adapt and improve its environmental performance to respond to the climate and ecological emergency. ..green (such as trees, planting, ..nesting opportunities for pollinators, bird and bat boxes) and blue water, (such as raingardens, ..) is needed to absorb surface water, absorb CO2, filter micro-particles, reduce urban heating and allow nature – with greater biodiversity—to permeate the city.

- /(p34)/- What do we want to achieve ..-is attractive, liveable – with a network of high quality public spaces linked by walkable streets, serving a diverse population – is healthy, inclusive and promotes well-being of all through ..civic spaces and green/blue infrastructure that encourages social cohesion, exercise, relaxation, play

Where we are now –

..a critical lack of public space .. Blythswood Square is not open for public use, the riverside is significantly underutilised and George Square lacks the quality and dignity …

/(p35)/- ..public realm. It is traffic dominated with little green relief; there are very few trees or raingardens .. ..hard public realm – with a lack of green/blue infrastructure – inhibits the survival of nature and stunts the natural biodiversity .. also inhibits surface water drainage .. need for .. the adaptation of the public realm —to manage surface water ..

(p36) – Priority issues.. –

Critical lack of public spaces (green, grey, blue) ..- ### Lack of ‘green’ throughout the centre, to detriment of nature networks, environmental performance and visual attractiveness ..- Traffic dominated ;. air, noise, visual pollution

How .. – High quality public space – as essential neighbourhood infrastructure

- Creation of new Public space creation ..prioritised…Pocket parks should be created ..to complement visitor attractions ..to encourage greater social interaction ..and promote community. The DRFs will explore opportunities for public space creation at district level .. key opportunities:

- (p37) -Sites with potential to incorporate public multifunctional open spaces. Including vacant / derelict land and surface car parking.

- (p38) Innovative design approaches in the creation of feature spaces and public realm will be encouraged that: – Create a variety of distinctive spaces that draw people to play and interact, provide shelter, shade, seating and rest areas, create a neighbourhood focal point and physical recreational opportunities – Green the city and promote biodiversity and nature based design solutions – Embody multi-functionality, climate responsive design and climate adaptation measures ..- Reflect the culture of the city through art, lighting, wayfinding and events spaces ..

- Activation of Public Space -/..to provide greater ‘round the clock’ activity. Public space and street frontages/..should be prioritised for activity.

- Environmental Engineering.. – adaption of the urban landscape to be climate resilient measures including; urban greening, tackling pedestrian, cycle ..movement, /../creation of green/ blue infrastructure, water management and ..renewable and sustainable heat and power sources.

- (p40) -(1) Increase ..canopy cover ..for carbon sequestering, improved air quality and urban cooling. (2) Moving from unipurpose vehicle dominated ..to dynamic connected green spaces for pedestrians with a diverse range of uses. (3) Capture storm water within newly formed landscapes and pocket parks. (25) Ground source heat-recovery from pavements and green spaces.

- (p42) – Green and Blue ..strategy for landscape and biodiversity improvement and adaptation (’greening the centre’) and surface water management. ..will include pocket parks,

- Open Space Strategy – all the city’s open spaces to meet a variety of functions, such as water retention, urban greening, sport and play, biodiversity enhancement or food growing. ..inform the Integrated Green/Blue Infrastructure Strategy for the Centre.

6. Spacial strategy

(p50) – placemaking priorities in collaboration with local stakeholders. – ..

- Create a range of high quality public spaces – from child’s play to tranquil oases

- Ensure Pedestrian priority and friendliness – create a walkable and cycle-friendly streetscape –

- Green the public realm, ..introducing integral green infrastructure –

- Provide multifunctional ..and climate responsive/ resilient development, that addresses microclimate, manages surface water and climatic change impacts

Merchant City –

- Extend and reinforce community ..and supporting community amenities, leisure uses and new public spaces – Realise the development of vacant land and gap sites –

References

(a) Health Benefits from the outdoors and nature, Scottish Natural Heritage (https://www.nature.scot/sites/default/files/2019-10/Guidance%20-%20health%20benefits%20from%20green%20exercise.pdf)

(b) Evidence Statement on the links between natural environments and human health, DEFRA 2017 (https://beyondgreenspace.files.wordpress.com/2017/03/evidence-statement-on-the-links-between-natural-environments-and-human-health1.pdf)

(C) A Dose of Nature – Addressing chronic health conditions by using the environment, University of Exeter (http://nhsforest.org/sites/default/files/Dose_of_Nature_evidence_report_0.pdf)

(d) Gladwell, V.F., Brown, D.K., Wood, C. et al. The great outdoors: how a green exercise environment can benefit all. Extrem Physiol Med 2, 3 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/2046-7648-2-3

(e) E. Coombs, A. Jones, & Hillsdon. M., 2010. Objectively measured green space access, green space use, physical activity and overweight.’ Society of Science and Medicine. 70(6):816-22

(f) EVIDENCE OF BENEFITS | NHS Foresthttp://nhsforest.org/evidence-benefits

(g) Urban Trees | Trees for Cities

(H) Recreating parks: Securing the future of our urban green spaces (Social Market Foundation, May 2020)

(I) https://www.london.gov.uk/sites/default/files/11015viv_natural_capital_account_for_london_ v7_full_vis.pdf

(j) Calculating the value of Edinburgh’s Parks (http://www.socialvalueuk.org/app/uploads/2017/09/CEC_SROI_Technical_report___final.pdf )